-

Par Lily42 le 26 Janvier 2008 à 00:36

Remembering Africans in the Nazi Camps : Theo Wonja I was 18 when I was sent to the labor camps.

[ Hambourg - ]

T.Wonja Michael was born in Berlin.In early 1943, Michael was marched with other Afro-Germans into a forced-labor camp near Berlin. Theo survived the Nazi terror and is still alive. Many other germans Cameroonians like M.Dibobe, Erika N'gando were deported and murdered in concentration camps.

T.Wonja Michael was born in Berlin in 1925. Their Cameroonian father, Theophilus Wonja Michael arrived in Berlin in 1894 and had four children with his German wife Martha Wegner. In early 1943, Michael was marched with other Afro-Germans into a forced-labor camp near Berlin.He was there until the camp was liberated by Russian soldiers in June 1945." His three siblings fled to France after "Negroids" were declared "undesirable" in 1936, but Michael chose to remain apparently, out of sheer stubbornness. He worked as a bellhop at Berlin's Hotel Excelsior (before being kicked out by a Nazi guest).The Nazis cast him in a tiny but very visible role in Germany's first color film released in 1943. "Muenchhausen"- which showed him cooling dignitaries with a feathered fan. Later he learned that the movie had been commissioned by propaganda Goebbels and would be used against blacks."In many ways, being a curiosity is just as bad as being a target I happen to be black, but I am German, and I insist on the recognition,"says Michael. Theodoro survived the Nazi terror and is still alive. Many other germans Cameroonians like Martin Dibobe, Erika, N'gando were deported and murdered in concentration camps.

German Of Color

Theodor Wonja Michael, gray-whiskered, Hemingway-like, stands alone behind a lectern on Howard University's campus. He has a story that he doesn't like to tell, but it is history, and so he must speak. The students have eagerly packed Ralph Bunche Hall on Sixth Street NW.

The lecture is billed as "German-African Relations--A Retrospective From the Colonial Period Until Unification." But they haven't come to hear the lecture. All week there has been talk about the Afro-German who has come to campus, the black survivor of the Holocaust. All week he has shaken up concepts of national and racial identity for hundreds of students.

So they have come again, this last day, for the flesh and blood of history, not the academic analysis that Michael (pronounced Me-Kel), with his master's degree in political science and German-accented, Shakespearean-trained voice, can offer.

They would much rather have the soul of this 75-year-old black man who survived two years in a Nazi labor camp, and who today still proudly declares his German-ness, who is committed to helping his nation understand him as a German who happens to be black. For some in the audience, it is news that there are Afro-Germans at all--currently between 100,000 and 200,000--let alone World War II survivors such as Michael.

"In many ways, being a curiosity is just as bad as being a target--I happen to be black, but I am German, and I insist on the recognition," says Michael, the son of a white German mother and a black immigrant Cameroonian father. He had come to Washington last week as the guest of the university's Department of Modern Languages and Literature. Professor Yvonne Poser says he was invited to "help our efforts to integrate black German history and culture in our German curriculum and to foster a dialogue between blacks in Germany and the Howard community."

There are as many forms of discrimination as there are black identities, Michael tells his audience, and being obsessed by it, or trying to emulate whites, is self-defeating and pointless, in Germany or the United States. The students listen intently, as if before them, as Michael says, stands "the eccentric grandfather they never knew they had." "In Germany, I am still stared at; even more so when people hear my accent," Michael will say later. His skin is the color of raw leather at sunset. "Here, no one observes me, which is wonderful. I prefer to think of myself as purely German. Without color. But looking for directions here, I noticed that I approached an African American on the street. . . .

It was like I was meeting cousins." Michael doesn't like to talk about those years when millions of Jewish people were being marched off to their deaths, when being gay was a crime and being black left you completely exposed and vulnerable. With no community, he couldn't fight. With confiscated papers, he couldn't run. With black skin, he couldn't hide.

And knowing that other Afro-Germans were being sterilized and executed, he couldn't hope for anything better than humiliation and bone-jarring labor in a war munitions factory. He meets the students' eager and sometimes heated questions with answers that swing between passion and a chilling matter-of-factness: Did black Germans unite against the Nazis? "No, we stayed apart from each other for fear that the Nazis would see us as a threat."

Does Michael's "community" demonstrate against racism in modern-day Germany? "No, we are still apart--we have no community in the American sense." Have German blacks retained any of their African culture? "Have African Americans retained any of theirs?--No, we have not, except for cooking!" Shouldn't Germany pay reparations now to its exploited former colonies in Africa? "Reparations for what? You cannot compensate for this treatment. You can't change people's minds. It happened, and that's all. All you can do is make [Germans] aware of what happened." Afiya Brent-Kirk, 20, a Howard biology major, is one of the curious Who have come to hear

Michael. "I'd never heard of a black German," she says later. "It's bad enough in the States, but he has to deal with racism without the help of masses of people in the same situation. I'm surprised he isn't more militant, that he's still so proud of being German." - - - Michael appears in a British documentary called "Black Survivors of The Holocaust," and he describes his visit to the nation's Holocaust Museum as a "happy surprise." "There were lots of papers on the Afro-German situation under the Nazis--I was amazed at the volume," he says.

"Of course, what they say is not known in America. In fact, I am puzzled about how little Americans seem to know about Africa in general." Peter Black, the museum's senior historian, says no figures are available for the number of black deaths in Germany during World War II. "The only figure we have is that between 385 and 500 people of African descent were forcibly sterilized by the Nazis."

Michael was born in Berlin in 1925. His mother died in 1926 and his father--a circus performer--died in 1934. Michael and his sister were taken in by his father's circus colleagues. His three siblings fled to France after "Negroids" were declared "undesirable" in 1936, but Michael chose to remain--apparently, out of sheer stubbornness. He worked as a bellhop at Berlin's Hotel Excelsior (before being kicked out by a Nazi guest).

He was also an aspiring actor and eventually found work. The Nazis cast him in a tiny but very visible role in Germany's first color film released in 1943--"Muenchhausen"--which showed him cooling dignitaries with a feathered fan. Later he learned that the movie had been commissioned by propaganda minister Josef Goebbels and would be used against blacks. "They trained me--and it is, of course, extremely ironic that it was the Nazis who gave me my big break!"

Michael says, his laugh nervous and unconvincing. He was 18 when he was sent to the labor camps. Michael had actually been conscripted, but when officials saw him he was immediately rejected. In early 1943, Michael was marched with other Afro-Germans into a forced-labor camp near Berlin, where he was effectively enslaved,working 72 hours a week at a munitions factory. He was there until the camp was liberated by Russian soldiers in June 1945. In 1998, he told a German Life magazine: "One must remember that the Damocles' sword of sterilization always dangled above us blacks in those years. It's why I was so afraid of going to the hospital. "Escape was not possible, certainly not if you looked like me.

Those who tried to get away were caught and put straight in a concentration camp. Usually they didn't survive." At Howard, though, he is not as forthcoming. He is careful, however, to draw a clear distinction between the labor and concentration camps. And just how did he manage his own survival? "God's help. Complying. Being inconspicuous, even with this," he mumbles, touching his cheek with the haunted look of a man who seemed never to have had that question fully answered.

After the war, Michael worked as a gofer for U.S. forces in Berlin for two years. In 1947, he married a white German woman. In the odd way that life can twist and turn, since those years, Michael has become one of Germany's foremost Shakespearean stage actors. In 1949, he took advantage of his dubious acting debut and returned to the profession. He had wanted to be an actor long before the Nazi film.

He also returned to school, eventually receiving his master's from the Institute of Economics and Politics in Hamburg. He rediscovered his African heritage in the 1960s, with frequent trips to Africa, a job editing a journal called Africa-Bulletin and the role of economics adviser to new German development projects in Niger, Ghana and Nigeria.

"You cannot force opinions to change--in fact, it makes me very angry when I see black people in minorities complaining that they have been treated this way or that," he says. Instead, blacks should "be proud of your history and of being black, and use the law if something criminal is done to you--force these supposed liberal countries to practice what they preach in the law books." His stage career has led to principal roles at mainstream German theaters in "Twelfth Night," "Taming of the Shrew" and "The Tempest," as well as contemporary German productions of "I'm Not Rappaport" and "Driving Miss Daisy."

He is currently rehearsing for his role of Talbot, the Earl of Shrewsbury, in Schiller's "Mary Stuart," to be staged next month in Cologne. The stage, he says, is a platform for art, not politics.

But his Career tells a different story. In "The Tempest," for instance--performing the role of Prospero--he persuaded the director to cast the Duke of Milan as a black man and his deformed slave, Caliban, as white. And in "Driving Miss Daisy," he enhanced the fond but prickly relationship of the black chauffeur with his white Georgian employer to "somewhat of a romance, a love story."

Stephanie Webb, 19, a Howard major in administrative justice, found Michael "completely amazing--it's one thing to experience struggle as a black person, but he's just experienced one kind of weirdness on another; treated like a freak." Another student, Brooke Anderson, a finance major, would later write, "Our discussion showed how much we emphasize skin color here. In the U.S., we are African Americans.

In Germany, they are just Germans with black skin. That gives us a lot of insight about who we are." With three adult children, Michael now lives with his second wifealso a white German--in Cologne. "I walk a lot and rehearse, but that must soon make way because I wish to write my memoirs," he says. "It'll be about a German, not an African."

But in the end, Michael seems to defy categories, racial or otherwise. "Which character that you've played echoes your life?" a reporter asks. Weary of all the questions, he is already rising to leave. "None! Not even close!" he answers. "Okay, which character in all of theater?" Michael stops in the doorway, turns, nods slowly and before stepping out onto Sixth Street, utters his answer: "Faust."

© 2000 The Washington Post Rowan Philp Washington Post Staff Writer Monday , October 23, 2000

Black Germans do not exist

Conventional history says the African presence in Germany goes back only a few decades. But that is not what the African-American historian, Paulette Reed Anderson, has just discovered. Her new work, Rewriting The Footnotes - Berlin and The African Diaspora, published in March, has proved conclusively that Africans have been living in Berlin since the mid-1880s, and in fact, 2,000 of them were killed in the Nazi concentration camps.

Osei Boateng reports. To this day, German historiography has taken insufficient notice of them; people of African descent or Black Germans. This is the case although they have a history dating back more than one hundred years in our country, says the German Commissioner for Foreigners Affairs, Barbara John, in the introduction to Paulette Reed-Andersons Rewriting The Footnotes Berlin and The African Diaspora.

Theophilus Wonja Michael arrived in Berlin in 1894 and had four children with his German wife Martha (née Wegner)

In contrast to popular opinion, Barbara continues, African immigrants did not first come to us in recent decades; the roots of Black Berliners go back much further and are closely connected to the history of the slave trade and colonial history, but also to the history of liberation and human rights movements. And so it is that the largely ignored subject of the Black victims of National Socialism [Nazism], has only been reappraised in the last few years.

Like the Jewish Germans or German Gypsies and Romany, Black Germans were also robbed of their human dignity during the period of the Nazi tyranny, deprived of their German nationality; many were deported and murdered in concentration camps. When Hitler came to power in 1933, Germany had a sizable black population.

By the time he was defeated in 1945, only a few scores remained 2,000 of them had indeed been killed in the Nazi concentration camps with the Jews and others. The offspring of the Black Germans were even sterilised under the Nuernberger Laws (or Citizenship Laws) of September 1935 passed to protect German blood and German honour. Under these laws, marriages between Aryans and non-Aryans were banned, and black Germans and their spouses lost their German citizenship and the right to claim state support such as unemployment benefits.

The sterilisation was to prevent the Black Germans from having children with Aryan Germans. Such a child was considered impure or not German enough. Thanks to Paulette Reed-Anderson, this despicable history of German mistreatment of its black population is now coming out. And Paulette deserves every bit of the encomiums that Barbara John pours on her in the introduction to Rewriting The Footnotes. Barbara tells how Paulette searched for and found material in libraries, archives and institutes for this publication.

She has brought together information stretching back over more than a century on the traces of the African Diaspora, people from Africa, the Caribbean, Latin America and the United States who lived in Berlin and have left their imprint on the history of the city. They include internationally renowned personalities, artists, musicians and scientists. The lack of recognition of their written cultural heritage, Paulette writes herself, has had adverse effects on the place of [people] of African descent in German society and the development of [their] cultural identity.

No basis for an inter-cultural discussion about the written contribution of [Black Germans] has been established, because the prevailing impression is that people of African descent have no written tradition in the German language and thus have achieved nothing that is noteworthy. But Paulette has discovered a good volume of work by Africans in Germany dating as far back as the imperial and colonial periods (1871-1914).

The writers include Anton Wilhelm Amo, from Axim, Ghana; Amur bin Nasur bin Amur Ilomeiri, a Tanzanian; Mary Church Terrell, an African-American; Paul Mpundo Njassam Akwa, Adolf Ngoso Din, Martin Dibobe (all Cameroonians); and letters by Mdachi bin Scharifu, a Tanzanian, and Thomas Manga Awka, a Cameroonian.

The experiences of black contemporaries in Germany during the Hitler are also described by George Padmore, (born Malcolm Nurse in Trinidad), the famous author, trade unionist and anti-colonialist who lived in Germany at the beginning of the 1930s.

Between 1930-1934, Padmore was the editor of The Negro Worker, a newspaper published in Hamburg. The experiences of Black Germans under Hilter are also described by Kwassi Bruce, a Togolese taken to Germany as a three-year-old in 1896 by his father; and William Edward Burghardt Du Bois (better known by his initials, W.E.B.), the African-American scholar, anti-colonialist and civil rights activist who lived in Berlin from 1892 to 1894 while studying philosophy at the Royal Friedrich Wilhelm University.

There but not there All these Africans left their marks in Germany, but you will never know from looking at Germany of today. It is amazing that in spite of the long association with Africa, and the fact that Africans and people of African descent have continued to live in Germany in their hundreds of thousands over the last 50 years, Germany can still today field all-white national football, athletics and Olympic teams. America, Britain, Canada, France, Portugal, Brazil, The Netherlands, etc, all have mixed teams, even Denmark has had to import a Kenyan runner (Sam Kipketer) and given him citizenship.

And Germany does have today a sizeable black population! Amazingly, none of them is good enough to break into the German national teams. Incredible! Perhaps the past has a lot to do with it. Kwassi Bruce, provides some clues in his writings. Kwassis father, J.C. Bruce (born Nayo Friko) was part of a 100-strong group of African contract workers brought to Berlin in 1896 from all over the German colonies in Africa to participate in the First German Colonial Exhibition held between April and November 1896.

Kwassi became a fine pianist and thrilled the crowds in Berlin, but things fell apart for him and the black population when Hitler came to power. Kwassi bequeathed to posterity a 10-page typewritten letter which he sent in August 1934 to the director of the Colonial Department of the German Foreign Office. He wrote: After [Hilters] national government took power, all Africans were required to present their passports and identity documents respectively to be verified.

Those who had not acquired German citizenship through a naturalisation process had their hitherto recorded German identification documents taken away and exchanged for alien passports. Since the beginning of the national government, we Coloured, insofar as we earned our own living as workers, have all, almost without exception, lost our positions and engagements respectively.

It has not been possible for us, even after presenting proof of our origin from the former German colonies, to get new employment... I am a naturalised German (my passport has not yet been taken from me). During the takeover of power by the national government, I played with my orchestra and was director of the same in a good Berlin wine restaurant. My position was permanent. Last March, the owner of the business told me that he regretted that he would not be able to employ me further with my orchestra because we were Coloured.

On the first of April, I had to stop [work] and tried to find a new engagement. In vain. Wherever I asked about employment, I was told that they regretted that they would not be able to employ me because I was Coloured. When I referred to my heritage from the former German protectorate [of] Togo, I received the following answer: Yes, we dont have colonies anymore, or Negroes are not allowed to be employed anymore, or The public doesnt want to see any more Negroes, we have to take the wishes of the guests into account. Even my participation in the [First] World War on the side of the Germans as a war volunteer as well as two years as a prisoner of war couldnt convince any employer to hire me. Kwassi was lucky, he still had his passport; others were not so lucky.

One of them was James Wonja Michael. He was born in Berlin in 1916 with three other siblings, Juliana (born in 1921) and Christiana and Theodor. James and Juliana survived the Nazi terror and are still alive. Their Cameroonian father, Theophilus Wonja Michael arrived in Berlin in 1894 and had four children with his German wife Martha (née Wegner). The children separated when their mother and father died in 1926 and 1934 respectively. James and Juliana went to live in France by separate routes and were reunited in the 1960s.

In the summer of 1994, James told Paulette Reed-Anderson while researching Rewriting The Footnotes: [It] was in 1937. We were in Paris... My passport had just run out, so I went to the German consulate to have it renewed... What do you want, the clerk demanded. To renew my passport, I answered. Your passport?!, he said. What are you, are you German? Yes, here is my passport, I answered. He examined it. Born in Berlin on 2 October 1916 and so on and so forth. Then he took my passport and went away with it.

A quarter of an hour or more went by before he returned but without my passport. I said: I thought you were going to give my passport back to me. He said: No, we are going to keep your passport. You are no longer German. Black Germans do not exist. Then, I was really angry. What was I supposed to do without identity documents and such? Nothing! How could I prove that I was really born in Berlin? This was the worst moment in my life...

In the beginning German interaction with Africa and people of African descent, according to Paulettes research, goes back four centuries. In 1681, ships from Bradenburg reached the West African coast where the Germans signed trade and protection treaties with the African rulers. A year later, the Bradenburg-African Company, a trading society, was formed.

One of its first activities was to ship African slaves to Hamburg at the behest of the Elector of Brandenburg, Prince Friedrich Wilhelm, who asked for 40 slaves to be transported to Hamburg. In 1684, Prince Jancke (a German spelling of the Ghanaian, Yankee) travelled to Berlin to visit Prince Friedrich Wilhelm (reign 1640-1688).

The following year, a treaty was signed between Bradenburg and the Danish West-Indian Guinea Company for a trade concession and the sale of African slaves on the Caribbean island of St. Thomas. By 1707, the Prussian military was training Moors as military musicians, again, at the behest of the king. Around that time and for most of the 18th century, the word Moor (or Mohr in German) was used to describe dark-skinned Africans.

The Germans even named one street in the Berlin district of Mitte for the Moors MohrenStrasse (Moors Street). In 1711, the Bradenburg-Prussian Trading Company became the exclusive property of the monarch. When Friedrich Wilhelm I von Preussen succeeded the throne (reign 1713-1740), he signed a treaty with Holland in 1717 for the sale of the Prussian trading base in West Africa. In 1729, Anton Wilhelm Amo (from Axim, in modern Ghana) who lived in Halle (Germany) published The Rights of Moors in Europe. Seven years later (in 1736), Amo was hired as a lecturer at the Faculty of Philosophy of Halle University.

They loved his work so much that in 1739, the University of Jena hired him as well to teach philosophy. In 1794, slavery was abolished in the Prussian States by the General Land Rights Laws. This was followed in 1836 by regular trade between the German independent cities of Bremen and Hamburg with West Africa. Following the Berlin Revolution of 1848, and the formation of the North German Confederation in 1866, Berlin became the capital of the Confederation in 1867.

Article 4 of the Confederations constitution authorised the acquisition of overseas territories. Two years later (in 1868), a branch of the Hamburg trading company, Carl Woermann, was established in Cameroon. German colonialism was about to spring its head. In 1871, the Second German Reich was proclaimed in Versailles, and Otto von Bismarck became chancellor until 1890. The old Article 4 of the constitution of the North German Confederation that authorised the acquisition of overseas territories was incorporated wholesale into the constitution of the Second Reich. The freedom to roam and seek overseas territories was thus guaranteed. In 1877, the first exhibition of Exotic Peoples (Nubians from Sudan and Egypt) was held in Berlin.

The exhibition later moved to Hamburg, Frankfurt, Dresden and London. The Africans were exhibited like animals in a zoo. A year later, the first German Colonial Congress was held in Berlin, during which the exhibition of Exotic Peoples (Nubians as usual) was repeated in both Berlin and at the Oktoberfest in Munich. In 1884, a battle was fought between German company owners in Togo and a group supporting the Togolese official, Lawson.

The German navy kidnapped three of Lawsons comrades-in-arms and transported them to Germany where they were detained in the barracks of the Second Guard Regiment in Berlin-Spandau until June 1884. The following month (July 1884), Germany formally proclaimed its first African colony, Togo. That same month saw a treaty between Cameroonian officials and the Hamburg trading companies, Carl Woermann and Jantzen & Thormaehlen. That treaty led to Cameroon becoming a German colony. But it did not take long for native dissatisfaction to surface. A full scale revolt against the Carl Woermann treaty happened in Duala in 1884.

In 1902, delegations from Duala under the leadership of Rudolf Duala Manga Bell and King Dika Akwa went to Berlin to address the Woermann treaty, but they were only able to present petitions to the Colonial Office. Though they asked their representative, Ludwig Mpundo Akwa, to press on the issue in Berlin, it could not be resolved and the petition movement continued until 1914. The dissatisfaction simmered until August 1914 when the Germans brought a charge of high treason against Manga Bell and Ludwig Mpundo Akwa.

After a secret trial without defence lawyers, Manga Bell, Mpundo Awka and 200 other Cameroonian leaders were hanged by the Germans. Having had their way in Cameroon, the Germans pressed on to modern day Namibia where they formally proclaimed the colony of German South West Africa in August 1884.

Three months later, (in November 1884), the Germans hosted the first of the conferences that led to the European scramble for Africa. The conference was initially called the Berlin West Africa Conference (or Congo Conference, for short). When it finally ended in February 1885, the Europeans had agreed among themselves trading treaties and the division of Africa into European zones of influence. As soon as the conference ended, the Germans proclaimed the colony of German East Africa (now Tanzania) in February 1885.

A year later, the Second German Colonial Congress was held in Berlin. The colonies were so profitable that in 1890, Berlin felt the need to establish a Colonial Department in the Foreign Office to look after the colonies. But the people of the colonies were less than happy. In 1888, revolts against German rule started in Togo and went on intermittently until 1912. Similar revolts occurred in Tanzania from 1890 until 1898, and in Cameroon in 1891 until 1907. In 1896, Germany held its First Colonial Exhibition in Treptower Park in Berlin during which about 100 African contract workers from all over the German colonies were brought to Berlin.

This was the exhibition that Kwassi Bruces father, J.C. Bruce, attended with his family, including the three-year-old Kwassi. That same year, the Exhibition of Exotic Peoples was repeated in Berlin, this time with a harem from Tunisia. It was followed by yet another Exotic Peoples exhibition in the Hamburg Cathedral starring, as they billed it, 33 wild women from Dahomey. By 1898, the German colonial policies were causing a lot of angst in Africa, such that a petition from Cameroon was presented to Kaiser Wilhelm II by the president of the African Association in London, Henry Sylvester Williams.

The Germans reacted by naming a street in the Berlin district of Wedding after Cameroon KamerunerStrasse. The following year, another street in Wedding was named after Togo TogoStrasse. The street naming in Wedding continued unabated in 1903, the Guinea Coast of West Africa (then variously called Pepper Coast, Gold Coast, Slave Coast) got GuineaStrasse, in 1906 it was the turn of the whole of Africa AfrikanischeStrasse; then in 1927 DualaStrasse after Duala, UgandaStrasse after Uganda, SambesiStrasse after River Zambezi, SenegalStasse after Senegal and TangaStrasse after Tanganyika (now Tanzania). But if the Germans thought the street naming in Berlin would mollify the Africans, they had not seen nothing yet. The German East Africans revolted big time in what became known as the Maji Maji rebellion that went on until 1908 and saw over 200,000 people killed in the region. Similarly, in 1904, the Hereros in Namibia revolted against the seizure of their land by the Germans. The Nama tribe later joined the revolt, and in a space of a few crazy months, the Germans massacred (or caused the death of) over 65,000 of the 80,000 Herero population. To this day, the Germans have refused to pay reparations to the Herero, even though Berlin has been paying reparations to the Jewish victims of the Hitler era. Echoes from the past The German attitude to the peoples of its African colonies appears to have been informed by the way Europeans perceived Africans at the time. An article discovered by Paulette Reed-Anderson published in 1913 by the Koloniale Rundschau titled, Africans in Europe, eloquently summed up the German governments position on the Africans. In our colonies, the article said, the existing educational opportunities will be sufficient for the natives for a foreseeable time period and therefore their attendance at schools in Germany is out of the question. It is reasonable to expect that the presence of blacks at institutes of higher education in Germany would be disadvantageous. But disadvantageous to whom?

The article did not say, but nobody is fooled. Paulette tries to put it in perspective: After the founding of the [German] empire, she says, two economic crises burdened the German economy. The first, from 1873 to 1879, and the second from 1882 to 1886 should, among other things, be seen in connection with the transformation from an agriculturally-based economic system to one based on industrial production. In order to drive industrialisation forward, the German government needed access to the global markets and a connection to the European and international banking sector.

The Berlin West Africa Conference [the Congo Conference that led to the scramble for Africa] should be seen in this context. From the total of 36 articles that were negotiated at the conference, all but five had to do with the regulation of trade between the contractual partners.

The entry into European colonial politics formed a political prerequisite that allowed the German government to achieve the transformation of the society from an agricultural to an industrial nation. Blacks in Germany The majority of the black men in Germany at the time found employment in the entertainment industry and only a few became skilled manual workers such as shoemarkers or cooks. The lucky ones, such as the Cameroonian, Martin Dibobe, became train drivers on what is now the Berlin subway. The women, on the other hand, were employed exclusively in the entertainment industry. By 1912, 1,800 blacks were registered as residents of Berlin alone. Paulette tries to explain why almost all the blacks worked in the entertainment industry: The first African slaves in Europe, she says, were used as field workers on the plantations of the Iberian Peninsula or they were forced to work as domestic servants for the nobility.

Like their counterparts in Britain, France and Holland, German nobles and wealthy merchants took Africans as serfs, domestic servants and soldiers. This image of the African slave or servant did not go away when slavery was abolished. It was followed by the development of ideologies that were just as restrictive and inhuman as slavery itself, Paulette adds. Throughout Europe and the Americas, she writes, scholars rendered their contribution to the development of prejudices and racial ideologies. In 1798 for example, the philosopher Christoph Meiners (1745-1810) from Goettingen wrote a book in which he sorted human beings into the categories of beautiful and ugly. Those who did not like the Europeans look light-skinned were sentenced to being ugly and half-civilised. When slavery was abolished in France in 1848, the philosopher, Carl Gustav Carus (1789-1869), who was born in Leipzig, published a book with another variation on the skin colour discussion.

According to Carus, the people of the earth should be divided into four races. These should be compared to a 24-hour day and differentiated according to bodily functions. He compared the white race to day and the brain. He compared the black race to night and the genitals. In 1859, when the Englishman Charles Robert Darwin (1809-1882) published his book, On the Origin of the Species by Means of Natural Selection, his theories about nature were transferred to human beings by his supporters.

This led to a new scientific social theory that formed, as Paulette says, the foundation and essential justification for the injustice, exclusion and genocide that has taken place since the 19th century... Increasingly, aggressive racism overshadowed the lives of people of African descent in Europe, the Americas and elsewhere. The Black Disgrace In 1886 when the American firm, Barber Asphalt Paving Company, won a contract to asphalt LandsbergerStrasse in the Berlin district of Mitte, the companys five black workers became the centre of attraction. The German newspaper, Illustrierte Zeitung, reported on 12 April 1886: They had brought five real Negroes. Usually the black brethren were stared at by crowds between apes and brightly coloured parrots as criers at the Hasenheide [a park] in front of groups of animals, tight ropes or promising but somewhat mystic cabinets.

One suddenly saw the Coloureds as street workers. Hundreds of curious bystanders surrounded the work site from morning until night... To have to accept these dark men of honour as industrious, skilful workers was very difficult for a certain part of the Berlin population. You can excuse the folk of 1886, but the German attitude to blacks did not change with the years. As late as 1931 when the film Hell on Earth was released with the African-American choreographer and artist, Louis Douglas, in a lead role, the film critic of the German newspaper, Deutsche Tageszeitung wrote: A Jazz Nigger from Paris teaches the soldiers of the white peoples peace! That is so dumb that it would be ridiculous in this bitterly serious time if it wasnt so embarrassingly deliberate.

This was despite the fact that during World War I, thousands of Africans in the colonies and in Germany itself had fought on the German side against the Allies. One such African soldier, Heipold Jansen, born in Cameroon in 1893, was an enlisted officer in the Prussian Army and fought throughout the First World War for the Germans.

After the War, when Germany lost its African colonies to France and Britain, many Africans participated in the struggle to win back the colonies for Germany. But that counted for nothing in the eyes of Duetsche Tageszeitung. What seemed to trouble the Germans most about the Africans was the stationing, after World War I, of French African troops in the Rhine region of Germany and the offspring that the Africans were about to leave behind.

The government of Chancellor Friedrich Ebert demanded that the African soldiers be removed from the Rhineland. The Africans were mainly Senegalese and Moroccans. Says Paulette Reed-Anderson: The presence of the French African troops in the Rhineland became a long running topic in German politics. The insulting expression Black Disgrace (Schwarze Schmach) was used up into the Nazi period, and had become a term that symbolised the rising racism in Germany that targeted all [people] of African descent. Life under Hitler When Hilter came to power in 1933, blacks in Germany were also confronted with the full force of the Nazi Rassenpolitik or racial policies.

The leading journal that targeted blacks was Neues Volk which was published by the Department of Population Policy and Race. It had a circulation of 140,000 at the end of 1934. The articles from 1933 made the Nazis attitude to blacks crystal clear. In one of them, the Neues Volk advocated the sterilisation of the offspring (the Germans called them Rhineland Bastards) of the French African soldiers stationed in the Rhine region.

In another article, the Neues Volk wrote: The people of the white race have thought up, invented, discovered so much, not only cars, airplanes and radios, no really all inventions and discoveries were made by the white race. The black race has lived in the world as long as the white and has not yet invented or discovered anything. In December 1936, the Nazi government passed the Law on the Hitler Youth (Gesetz uber die Hitlerjugend) that decreed that all German youths be included in the Hilter Youth brigade, except black German children.

An article in the Neues Volk hinted why the black children were excluded: Disdained and pitied in the groups of the old local populations, thrown out of the association of the native population, they make their laborious way between the two cultures. And even when they want to be and do good, the stamp of their heritage remains stronger than all efforts to achieve a new bearable lot. Today, we know of approximately 600 bastards on the Rhine, tomorrow it will be more. Their sorrow will be multiplied through their children a sorrow that can never be overcome.

Let this be said to open the eyes of those in whose hands it lies to prevent this suffering from increasing. This was around the time that George Padmore was editor of The Negro Worker based in Hamburg. In an editorial in its April-May 1933 issue, The Negro Worker warned: Most Negroes in Europe and America as well as in the colonies do not yet fully realise that fascism is the greatest danger which confronts not only the white worker, but is the most hostile movement against the Negro race. Soon after this warning, the Nazi organ, Nationalsozialistiche Monatshefte thundered: In each Negro, even in one of the kindest disposition, is the latent brute and primitive man who can be tamed neither by centuries of slavery, nor by an external varnish of civilisation. All assimilation, all education is bound to fail on account of the racial inborn features of the blood.

One can, therefore, understand why in the Southern States of America, sheer necessity compels the white race to act in an abhorent and perhaps even cruel manner against the Negroes. And of course, most of the Negroes that are lynched do not merit any regret. From its base in Hamburg, The Negro Worker responded: This is the sum total of the philosophy of the new saviours of Germany. The most recent attacks of the fascists upon Negroes in Germany occurred a few weeks ago. Shortly after the infamous Captain Goering, the right hand man of Hitler, assumed office, he ordered his men to round up all Negroes and deport them from Germany. Among the first ones to be arrested was Comrade Padmore...

[He] was dragged out of his bed by the Nazi police and imprisoned for about two weeks, during which time the Nazi raided the offices of the Negro workers Union and destroyed all their property. Padmore was afterwards deported. That was in 1933. By 1939, black entertainers had been banned from appearing in public and had to go underground to find work (strangely) in the German film studios where they were needed for the production of colonial propaganda films.

After the defeat of Hitler, Germanys black population started to slowly drift back. In the last 40 years, African immigrants have become even more visible in the country. In 1999, 300,600 Africans were registered as living in Germany. This represented 4.1% of the total German population. Last year, 15,061 Africans were registered as residents of Berlin alone (3.4% of the capitals population). These figures exclude children from mixed marriages (African/German, or African-American/German) because German nationality is passed on by blood (ie, if the mother is German, the child is German).

Between 1945 and 1958, over 8,000 mixed race children (father usually African-American soldier, mother German) were born in what was then West Germany. In reality, there are no statistics on black Germans as such, as anyone who receives naturalisation is counted as German (race is not a category used for the statistics because of the bad experience of the Nazis using the census information of that era for their non-Aryan cleansing). That said, the anti-black xenophobia in Germany has not gone away. Blacks are attacked and killed at will by neo-Nazi youths, especially in the former East Germany. Most ordinary Germans are outraged by this state of affairs.

Last year, over 100,000 Germans, including Chancellor Gerhard Schroder, marched in Berlin to protest against the rising tide of racism against blacks and other foreigners in the country. The march followed the killing of an Angolan in a Berlin park by neo-Nazi youths. Like Britain, France and The Netherlands, the German government might publicly show its unhappiness at the anti-black attacks, but it takes more than just mere words to rid the system of institutional racism.

Again, as in Britain where the Home Office (which deals with immigrants) admitted last year that it is institutionally racist and promised to work hard to make amends, Germany will have to do more to uproot institutional racism in the country (especially against blacks). For a start, how about the national football, athletics and Olympic teams? Black Germans do not exist indeed! (Rewriting The Footnotes Berlin and the African Diaspora, by Paulette Reed-Anderson is published in simultaneous English and German translation by Die Auslaenderbeauftragte des Senats (The

4 commentaires

4 commentaires

-

Par Lily42 le 7 Mars 2007 à 14:54

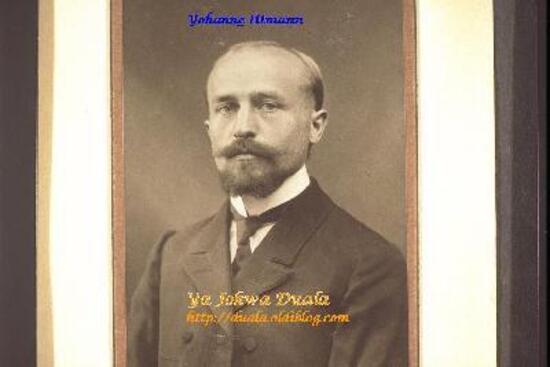

Linguiste

Die grammatik des Duala

Wörterbuch der duala sprache

Johannes Ittmann (26 January 1885 15 June 1963) was a German Protestant missionary in Cameroon between 1911 and 1940.

He was born in Groß-Umstadt, Hesse, Germany and died in Gambach, Hesse, Germany.

He did extensive ethnological and anthropological work in the Southwest Province, an English-speaking part of Cameroon, and published some 1,000 pages about it. His best known work is his dictionary about the Duala language.

votre commentaire

votre commentaire

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Par Lily42 le 8 Décembre 2006 à 11:53

Rédactrice en chefs du journal planète jeunes

Pourquoi je ne suis pas sur la photo ?

Edicef.

Oust les loups

Association Francis Bebey.

votre commentaire

votre commentaire

-

-

-

-

Par Lily42 le 10 Novembre 2006 à 23:42

Kalati:

Notice bibliographique de M. Issac Moumé Etia, premier écrivain camerounais,1940.<o:p></o:p>

<o:p> </o:p>

Site historiques de Douala, Tome I, 1940 ; Tome II, 1970.<o:p></o:p>

<o:p> </o:p>

Aperçu sur lAntiquité de Douala, 1940<o:p></o:p>

<o:p> </o:p>

Faux pas & Esprits légers , 1940<o:p></o:p>

<o:p> </o:p>

Simple réflexions : politique du Cameroun, 1970.<o:p></o:p>

<o:p> </o:p>

Deux Camerounais : Isaac Moumé Etia, Lotin a samè, 1970.<o:p></o:p>

<o:p> </o:p>

Les débuts du syndicalisme au cameroun, 1974.<o:p></o:p>

<o:p> </o:p>

Naisance du commerce au cameroun, tome I, 1974, tome II, 1977<o:p></o:p>

<o:p> </o:p>

Bwambo bwa Duala, 1978.Presence africaine ; Douala, Cameroun : Chez l'auteur, PL8141 .M68 1978 <o:p></o:p>

<o:p> </o:p>

<o:p>Grammaire abrégée de la langue douala 54 p. 13,5 x 18 cm<o:p></o:p></o:p>

Kuloto Kuloto çong : les transmissions chez les Duala, 1980.<o:p></o:p>

<o:p> </o:p>

Mbasà : contes et proverbes Duala, 1984.( avec cassette audio)<o:p></o:p><o:p></o:p>

<o:p> </o:p>

Rose porcelaine : poèmes, 1984.<o:p></o:p>

<o:p></o:p>

<o:p> </o:p>

Fleur de corail, 1987.

votre commentaire

votre commentaire

-

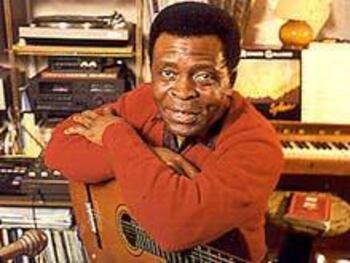

Par Lily42 le 10 Novembre 2006 à 23:42

Kalati

15 juillet 1929 (Douala) - 28 mai 2001 (Paris)

Lien : ***ICI***

Le fils d'Agatha Moudio (roman)

Editions Clé, Yaoundé, 1967.

Grand prix littéraire de l'Afrique noire 1968.

10ème édition en 1985.<o:p></o:p>Traductions :

· 1971 Anglais (Heinemann, London)

· 1971 Polonais (Czytelnik, Warsaw)

· 1973 Americain (Indpdt Publishers Group)· 1974 Russe

· 1987 Allemand (P. Hammer Verlag, Wuppertal) <o:p></o:p><o:p> </o:p>

<o:p>Trois petits cireurs</o:p>

<o:p>Editions Clé, Yaoundé, 1968.</o:p>

<o:p></o:p>

Embarras et Cie (nouvelles)

Editions Clé, Yaoundé, 1968.

2ème édition en 1970<o:p></o:p><o:p> </o:p>

Le petit fumeur (fiction jeunesse)

Editions Rencontres, Lausanne, 1969.<o:p></o:p><o:p></o:p>

Avril tout au long (poésie)

Editions Rencontres, Lausanne 1969.<o:p></o:p>Trois petits cireurs (fiction jeunesse)

Editions Clé, Yaoundé, 1972.<o:p></o:p><o:p></o:p>

La poupée Ashanti (roman)

Editions Clé, Yaoundé, 1973.

Traductions :

· 1977 Américain (Lawrence Hill & Co, Wesport, CT) The Ashanti Doll

· 1980 Russe <o:p></o:p><o:p></o:p>

Le roi Albert d'Effidi (roman)

Editions Clé, Yaoundé, 1976

Traductions :

· 1982 Américain (Lawrence Hill & Co, Westport, CT) King Albert

· 1980 Allemand (Peter Hammer Verlag, Wuppertal) <o:p></o:p><o:p></o:p>

Concert pour un vieux masque (poésie)

L'Harmattan, Paris, 1980.

Traduction :

· 1980 Allemand <o:p></o:p><o:p></o:p>

La nouvelle saison des fruits (poésie)

Nouvelles éditions Africaines, Dakar, 1980.<o:p></o:p><o:p> </o:p>

Contes de style moderne (conte)

Balafon, Air Afrique, 1985<o:p></o:p><o:p> </o:p>

La lune dans un seau tout rouge (nouvelles et contes)

Hatier, Paris, 1989.<o:p></o:p><o:p> </o:p>

Le ministre et le griot (roman)

Sépia, Paris, 1992.<o:p></o:p><o:p></o:p>

L'enfant-pluie (roman)

Sépia, Paris, 1994

Prix Saint-Exupéry.<o:p></o:p><o:p> </o:p>

<o:p> </o:p>

Congrès de griots à KanKan (théâtre)

Inédit 1994.

Joué à Lausanne (Suisse) en 1995.<o:p></o:p><o:p> </o:p>

La radiodiffusion en Afrique Noire (essai)

Saint Paul, Paris, 1963.<o:p></o:p><o:p></o:p>

Musique de l'Afrique (Essai)

Horizons de France, Paris, 1969.

Traduction :

1975 Américain, African music : a people's art, (Lawrence Hill & Co. CT 1975)

Rééditions régulières.<o:p></o:p> votre commentaire

votre commentaire Suivre le flux RSS des articles de cette rubrique

Suivre le flux RSS des articles de cette rubrique Suivre le flux RSS des commentaires de cette rubrique

Suivre le flux RSS des commentaires de cette rubrique

Tèmè ! Paña ! Ebanja mwènèn môngô mu ni sisea !